Introducing Doughnut Economics

The pioneering book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist was released by economist and author Kate Raworth in 2017. This groundbreaking work presented seven ways to rethink economics. The first way is to create a new goal for progress and prosperity in the 21st century, beyond the simple, outdated and problematic goal of growth at all costs. More than a vision, the Doughnut o ffers us a compass to navigate the complex social and ecological challenges that face humanity in the 21st century. Visualised as two concentric circles forming a doughnut ring, with our social foundation as the inner ring and the ecological boundaries as the outer ring, this vision presents a world in which people and planet can thrive in balance.

The Doughnut’s social foundation is derived from the social priorities laid out in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. In this way the inner ring of the Doughnut does not introduce new metrics or measures, but rather draws on and reflects the goals that all UN Member States agreed to in 2015. These include the essentials of life: elements like water, food, health, education, energy, income and work, peace and justice, housing and social equity. These elements are represented as 12 segments within the doughnut. In this vision of the future no one falls below this social foundation, or into the hole in the middle of the Doughnut.

The Doughnut’s ecological ceiling is made up of the nine planetary boundaries as defined by the Stockholm Resilience Centre. In a similar way to the Doughnut’s social foundation, this method does not introduce new science, but instead adopts an agreed way to measure our shared ecological boundary. This also identifies a range of ecological factors, going beyond a measure of climate change alone, to include elements like chemical pollution, land conversion, biodiversity loss and ocean acidification. In this vision of the future no human activity exceeds our ecological ceiling.

Between our social foundation and ecological ceiling we find the safe and just space for humanity. The Doughnut’s essence becomes clear: the goal for our governance, politics, economics, science, business and civil society should be to move humanity into this safe and just space.

Of course, the world is still far from operating in this space. Not only are billions of people unable to meet their basic human needs, we are already operating well beyond at least four of our planetary boundaries.

Our global challenge is to simultaneously meet the human needs and wellbeing of all, while also regenerating our planet and bringing our ecological impact back from our current overshoot. This challenge must be met by all actors and levels of government, including at a city scale. Cities around the world (including Amsterdam, Brussels, Copenhagen, Philadelphia and Portland) have risen to this challenge and have begun localising the Doughnut model to a city scale. This process has become known as creating a City Portrait and has led to the creation of innovative tools and processes that engage populations and guide decision makers.

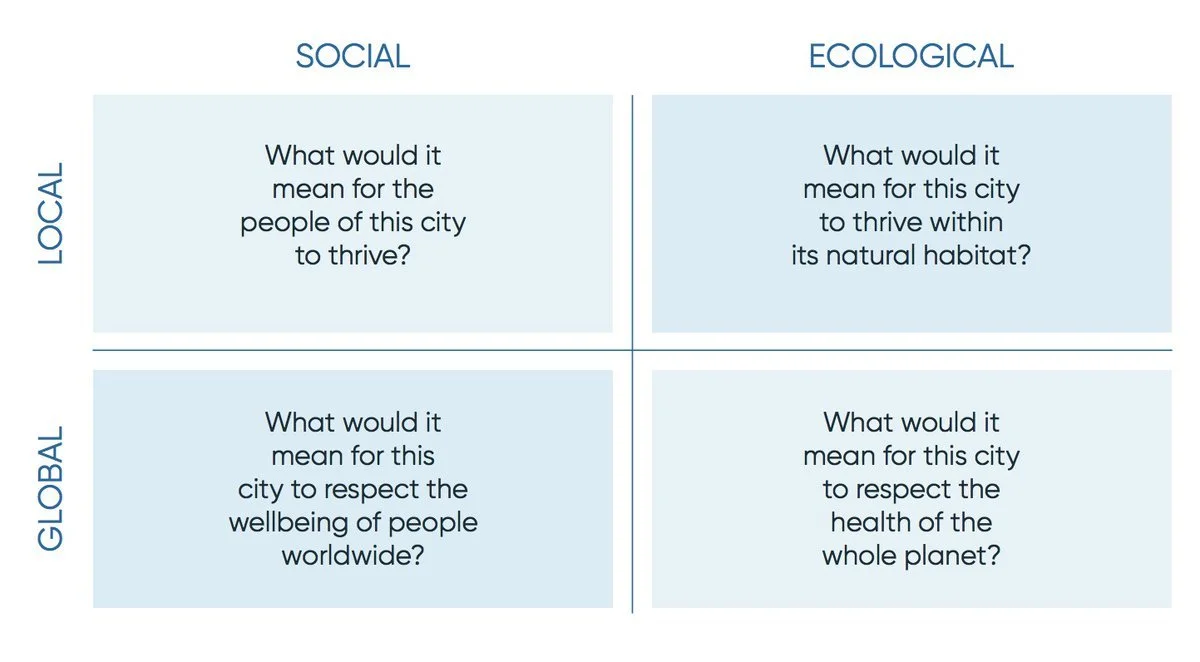

Here in Melbourne, we have been particularly inspired by the City Portrait process and have learned from the published City Portrait Methodology. The development of this process involved ‘downscaling’ the global lens of the original Doughnut and making it more accessible and relevant at a local scale. At the core of this process are four questions that citizens and institutions within a city can begin to explore:

On the local axis, the methodology asks what it would mean for the people of a city to thrive (Local-Social lens) and what it would mean for the city to thrive within its natural habitat (Local-Ecological lens). On the global axis, it asks what it would mean for the city to respect the wellbeing of people worldwide (Global-Social lens) and what it would mean for the city to respect the health of the whole planet (Global-Ecological lens). By breaking these questions down into local, global, social and ecological elements, the methodology provides an inviting and accessible entry point into considering complex issues, and an ability to begin mapping existing indicators for a localised version of the Doughnut.

Our work so far in Melbourne relates to the local axis of this framework; engaging with the global axis is part of our pathway ahead.

Finally, our work to date has focused on the first way to think like a 21st Century economist: creating a new, locally-adapted compass for social progress and prosperity in Melbourne. In order to do this, however, our work embraces a number of elements of the other seven ways of thinking (see below). These can be discovered at the Doughnut Economics Action Lab, a global community turning Doughnut Economics from a radical idea into transformative action, and in Kate Raworth’s Ted Talk below.