What exactly is climate change adaptation?

Having a shared understanding of what climate change adaptation is, is integral to doing the work effectively. To mark the relaunch of the Climate Change Exchange, Regen Melbourne’s Research Activation Lead, Yasmina Dkhissi, breaks down the nuances of climate adaptation.

Part of my role at Regen Melbourne is to bring a climate change adaptation lens to the work we do. Yet, through many conversations with researchers, policy makers, practitioners, community organisers and members, I’ve come to realise there isn’t always a shared understanding of what climate change adaptation means. It gets lost in the increasingly technical language surrounding climate science. And it’s often mistaken for action, when at it’s heart, it’s about the process.

This piece is designed to build a language bridge and provide a voice to the nuances of climate adaptation. As we embark on the process, together.

Why does climate change adaptation matter?

There is an urgent need to adapt to the already locked-in and future impacts of climate change, and reduce the harm caused to our communities and ecosystem. Our excessive pressures on the Earth’s natural systems are creating an imbalance that is worsening climate change and its effects on human and natural systems. This is why it is so crucial that we find effective, integrated and socio-ecologically just ways to adapt and care for our future.

Key climate adaptation take aways

To reach its full potential, climate change adaptation must be understood as a social process within a complex adaptive system

Adaptation is a socio-ecological process anchored in place

Adaptation requires integrated responses to interconnected issues

Adaptation is a relational process

Adaptation recognises uncertainty in decision making

Adaptation encourages us to learn our way forward

A Social Process within a complex adaptive system

To reach its full potential, climate change adaptation must be understood as a social process within a complex adaptive system, not as a singular intervention sitting in silo and disconnected from the rest of the systems and issues with which it intersects.

It helps to frame the process as part of a dynamic and relational system. Why? Because when we understand our socio-ecological system as a complex adaptive system that evolves dynamically over time in response to feedbacks and changes in the system context, we can start to see that behaviour which is non-linear, constituted relationally, and different from the sum of its individual parts, emerges (Stockholm Resilience, ‘Complex Adaptive Systems’). However, these days, policies, actions, plans or roadmaps tend to assume a static context and expect a linear behaviour into a known future (Hoffstetter, ‘Innovating in Complexity’). Unfortunately, such a deterministic and rigid approach is simply not good enough and not adapted to the reality of the world we live in – which is full of uncertainty and changing conditions.

“Adaptation is the process of cultivating and strengthening relationships both among humans and between humans and nature in a way that respects their innate interconnectivity. These relationships help identify, motivate and guide necessary adjustments to actual or expected climate and its effects in order to moderate harm and maximise the potential for those relationships to thrive.” – Goodwin et al., ‘Relational Turn in Climate Change Adaptation’.

This definition is rich in its substance, so let’s bring to life the key features it speaks to.

Adaptation is a socio-ecological process anchored in place

Place carries meaning, culture and stories. Place is also where action happens. The components that make up a place should be considered as key interconnected determinants for building adaptive capacity and taking effective action (Griffith University). The interactions between key determinants of adaptive capacity (economic resources, institutions, equity, infrastructure, social capital or technology) make sense in a place-based context; together with collaborative governance approaches that value local knowledge, different ways of knowing and encourage coordinated action.

The ways people understand, see and value places, vary across communities and organisations, and this is why to be ‘place-based’, adaptation must engage with diverse perspectives, values and timescales (DELWP, ‘Place-based Adaptations’). To me, this speaks to honouring the historical contexts within which we exist and the people who have come before. This also means being aware of who is or isn’t in the room, challenging how and by whom decisions are being made, creating spaces for challenging conversations and status quo, and for celebrating cultural strengths. In the Australian context, place anchoring of local adaptation calls for acknowledging what is good for Country and learning with First Nations ways of being, thinking and knowing. In his book, Sand Talk, Tyson Yunkaporta calls adaptation “the most important protocol of an agent in a sustainable system”, and speaks beautifully to the reciprocity and complex relational transformations that occur through interactions and intertwined ways of thinking and learning.

Adaptation requires integrated responses to interconnected issues

To adequately respond to the size of the interconnected climate change challenge, we need coordinated and integrated approaches that reflect the cross-sectoral nature of climate issues (Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in Suburban Melbourne, Greater Melbourne Climate Change Adaptation Snapshot) and support climate justice (Climate Justice in a Climate Changed World).

Ample evidence shows that negative climate change impacts are felt unevenly by different parts of our communities, and that compounding impacts and their flow-on effects will exacerbate existing vulnerabilities and further undermine our capacity to cope and adapt.

Yet, climate change does not exist in a vacuum. It's impacted by (and impacting) housing, food, water, transport and health issues among others – which means that to be fully effective, adaptation responses must be holistically co-designed with local and systemic understanding. This includes supporting robust understanding of climate change risks and impacts, as well as their connection to societal, economic, legal, political and ecological issues that need to be surfaced through research and insights from practitioners and local communities.

Adaptation is a relational process

Adaptation is a relational process, connecting people with each other and with nature.

“The most important unit of analysis in a system is not the part (e.g. individual, organisation, or institution), it’s the relationship between the parts.” – Brenda Zimmerman.

Systems are made of people. Relationships are at the essence of meaningful adaptive change. Systems change, like a sense of belonging to a shared vision or community, isn’t something that can be delivered through a single intervention, it’s a thread that ties individual outcomes to the fabric of collective transformation (SSIR & IDR). It needs spaces for people to connect, exchange ideas, learn and to co-create long-lasting contributions together.

Currently, there’s a massive disconnect between the worlds of decision and policy makers, researchers and community organisations who lack the time, space and capacity to meet and understand one another’s perspectives. This is hugely problematic. Because due to structural barriers and conflicting priorities, most seem to lack the time to dedicate to connecting with one another.

As I write these words, very aware of my privileged position, and with profound care and love for the many people who do what they can to contribute to creating fairer futures, I know how demanding this work is.

Yes, this deserves a pause, as we all deserve to rest.

Change that is created through relational work and a siloed approach – or one that fuels exhaustion – will only perpetuate the status quo. It’s vital for the people who do this important work that the need for adaptive capacity building is recognised at a systems level and embedded within people’s roles. This will allow for the work to be effective and flourish in ways that respect people’s capacity and humanity.

Adaptation recognises uncertainty in decision making

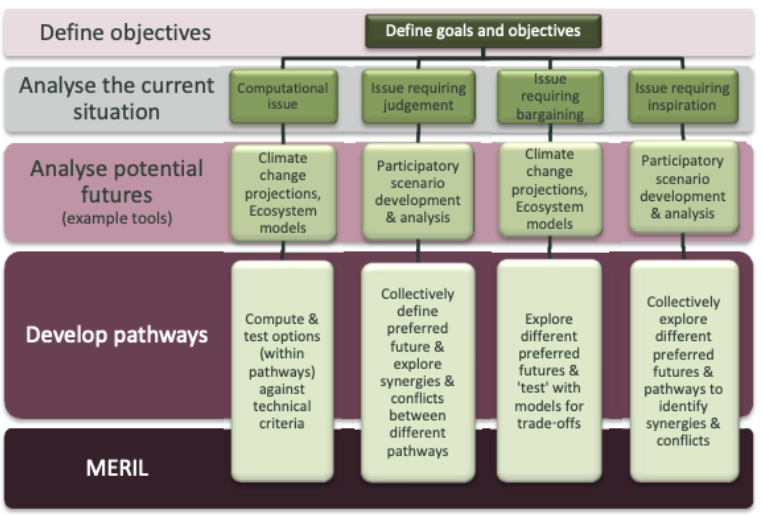

One aspect which is often overlooked, is that most plans are linearly built, considering actions towards an expected future. Let’s be honest, most of us love the illusion of control. However (and unfortunately), despite climate models, we can’t be certain of what the future holds. Uncertainties exist and are amplified by climate stressors and how these interact with cultural, economic, political and ecological contexts. This means that we need adaptive planning approaches that work with the unknown and allow us to make decisions under conditions of uncertainty, to experiment and learn as we go (‘Place-based Adaptation Concepts and Approaches’). The way we make decisions and plans must have built-in flexibility and include a proactive process to respond to change. Rather than one adaptation plan, we should have adaptation pathways and consider how options perform against a range of multiple possible futures and scenarios.

Similarly, adaptive policies offer a deliberate response where integration and foresight, multi-stakeholder governance, as well as monitoring, learning and evaluation practices, allow for better anticipation and policy adjustments under dynamic and uncertain conditions (Swanson & Bhadwal, ‘Creating Adaptive Policies’).

Adaptation encourages us to learn our way forward

Adaptation efforts include the ways in which the progress of these efforts are monitored and evaluated, while embedding the capacity to continuously learn and adapt initiatives throughout their implementation when the need arises (‘Monitoring, Evaluating and Learning for Place-based Approaches’). This means planning with flexibility, with the awareness that things will evolve, and that learning along the way will inform how to pivot depending on what the need and context are. For this to happen successfully, there’s a level of openness to mutual learning and understanding that people involved in the design of these interventions should bring with them – which can be supported through creating spaces for collective listening and hands-on iterative and participatory design process.

What are the processes?

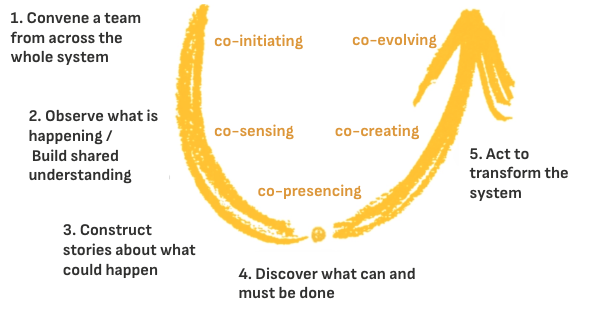

To give an example of an ‘adaptation process’, let’s take a look at Adam Kahane’s book Transformative Scenario Planning. Grounded in Otto Scharmer’s Theory U framework and practice, the approach offers an intuitive five-step process bringing together the needs of systemic climate change adaptation, and recognising that specific interventions and pathways will emerge from the process. It’s worth noting that before a meaningful process can be undertaken, understanding of a given system and building relational tissue is key.

Convene a team of people from across the whole system that together are able to influence the future of that system, bringing together a range of perspectives towards a shared vision and actions that will refine along the way.

Observe and build a shared understanding of what is happening in the system they seek to influence. This requires being open to listening to diverse perspectives, seeing with fresh eyes, sitting in discomfort and learning with others. This helps surface the most important uncertainties about the future that will help define scenarios in the next step.

Construct stories about what could happen in and around the system the team seeks to change, acknowledging that a range of potential futures exist. To be useful, the scenarios should be relevant, challenging, plausible and clear, in order to enable action across the system.

Discover what can and must be done thanks to the articulation of the scenarios. Actors will be able to identify whether they can directly influence the change, whether they need to partner to make it happen, or what they might need to do to adapt.

Act to transform the system with the members of the team and with others across the system. Transform the realisations co-learned through the process into priority actions (these might constitute a portfolio of connected activities).

What are the actions?

Actions can take a range of shapes and forms, including projects, campaigns, policies, legislation etc. In line with the Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction, actions include those taken in response to climate change impacts that lead to the reduction of risks (through the reduction of hazard, vulnerability and/or exposure) or a realisation of benefits (IPCC).

Where can we draw inspiration from?

We can draw inspiration from cities and people right around the world. This includes examples of anchoring climate change adaptation and justice in cultural heritage in Rotterdam; public participation process in Barcelona's Superblock’ concept; advancing climate equity in coastal climate change adaptation in Canada; or inspiring pathways thinking and Indigenous values embedded in adaptation approaches in New Zealand.

Doing climate change adaptation well is hard, but it’s not impossible. It’s our collective responsibility to practice and learn from one another to be in service of just climate change adaptation.

Where to from here?

To help us do just that, we’re bringing the Climate Change Exchange (CCE) back to life. The CCE exists to bring together research, policy and practice to build our cross-sectoral capacity to create inclusive, just and transformative adaptation futures.

The CCE supports rigorous and reflective collaboration among researchers, policy makers, practitioners and communities to help inform better policies, practices and decision making. It creates spaces for sharing, learning and connecting to build relationships, encourage critical thinking, challenge perspectives and enable collective and individual actions to transform systems.

Do you want to be part of growing the shared understanding and practice of adaptation, and together find effective, integrated and socially just ways to adapt and care for our future? Get involved here.